To

properly introduce the entry portal, I have to begin at the

surface. You can't naturally get to the subterranean tunnels,

domes and silos without first arriving at this area and so I shall

begin, quite logically, at the beginning.

The

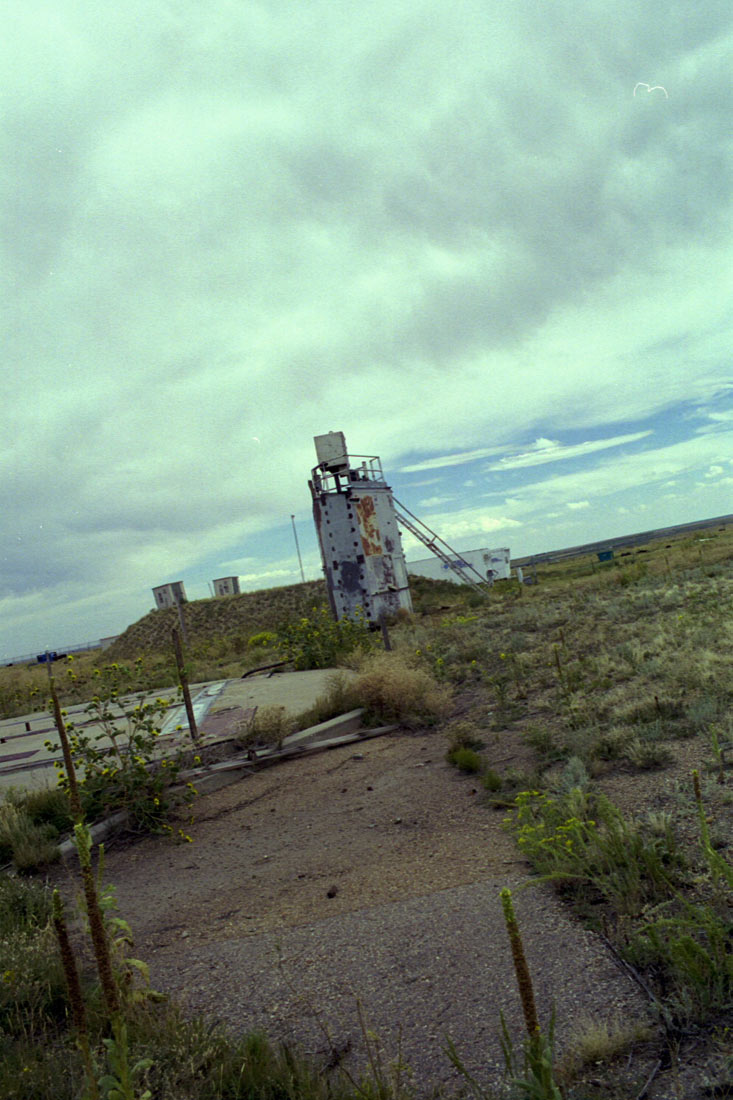

surface, once every bit a military installation and easily identifiable

as such, has been transformed by time. The concrete and asphalt at

Lowry 724-C are cracked, eroding, or just being steadily hidden beneath plant

life. Signs are faded or taken by the wind, and rust attacks every

speck of steel where paint has long peeled away. Concrete spalls

and cracks from the Winter cold and freezing, and all around evidence of

decay and reclamation by natural forces are rampant.

|

Lowry

724-C, circa 2002: The entry portal viewed from a nearby tower about 15

feet tall. The silo and its door are obvious in this westerly

view. At the right center, the concrete circle is the television

camera tube and at the lower right you can see the four circles of the

instrument assembly tubes which measured wind speed, radiation,

temperature and other important surface conditions.

The

personnel entrance is on the far side of the silo where, if you squint

really hard and use your super keen super vision, you can see me there

mooning the camera.

I

don't know where the tank came from, but it seems to be fairly recent

and not from inside the site. I think it had a date on it saying

it was manufactured in the 1990's.

Photo

courtesy of Sean Malloy

|

|

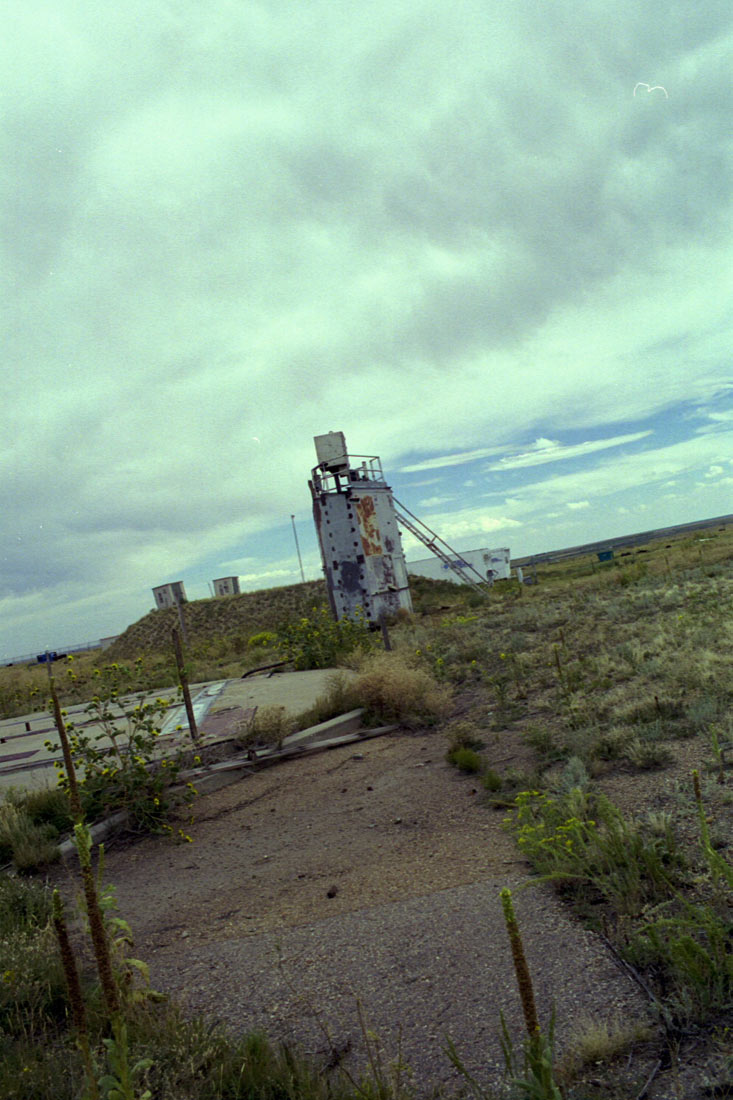

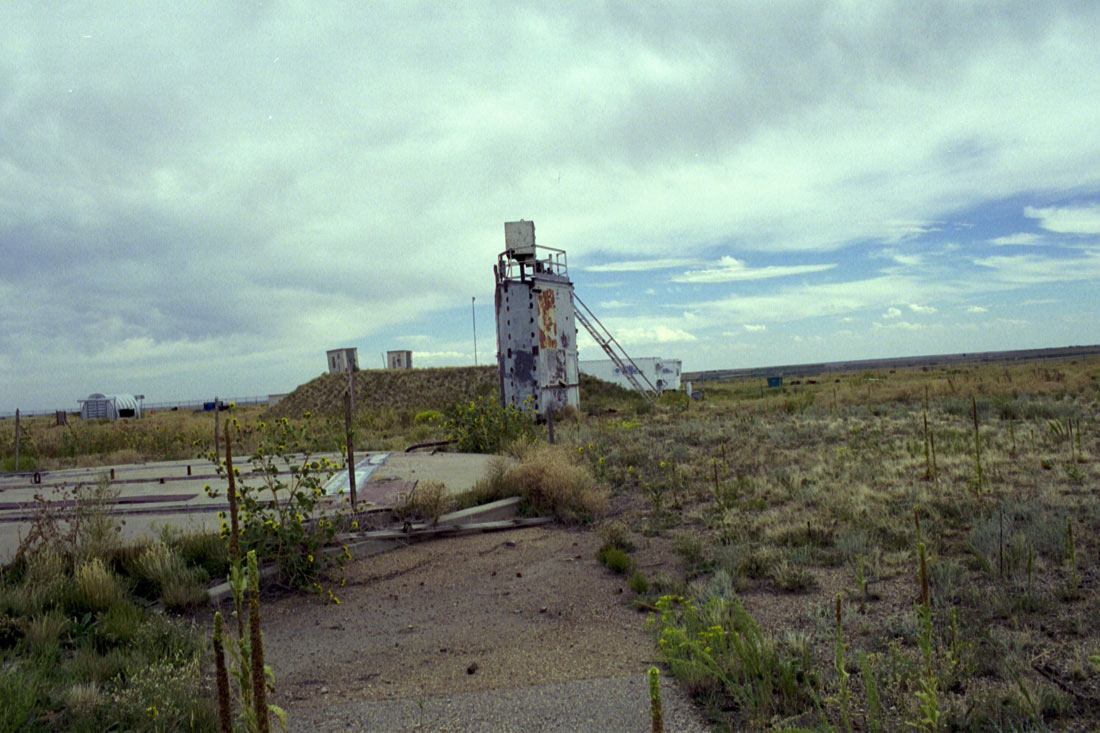

Lowry

724-C, 1999: A shot of the entry portal taken by a man with one leg a

foot shorter than the other.

This used to be all pavement here,

but as you can see, it has become seriously overgrown with scrubby

Colorado plant life.

|

|

Lowry

724-C, 1999: Portal and tower. The tower is actually constructed

from parts taken from the launcher silos. The bulk of this

structure is made up of the flame deflectors that were designed to

re-direct the exhaust from the missile to protect the missile platform

and silo during launch.

|

|

Lowry

724-C, 1999: Entry portal showing the silo doors, old and new personnel

entrances and the tower. Actually there are 2 such towers at 1-C;

the other is located near launcher #2. These towers appear to have

been used to photograph testing done on the surface by contractors after

the site's closure. The testing conducted was unrelated to missile

defense.

|

My

experience of first arriving at 724-C in the Fall of 1999 was one of

delight. Yeah, I find this stuff endlessly fascinating to the

extreme. The most minute of details which most people would never

care to know, I would likely find very interesting. So when I

arrived at the vast complex I was surrounded by mysteries, strange

structures and forms-- some completely obvious, and others completely

enigmatic.

I

spent several hours looking at everything I saw with the sort of

curiosity you'd expect from an alien who'd just landed on the site as

part of an anthropological study.

|

Lowry

724-C, 1999: A better view of the current entrance. This is a

somewhat northeasterly view.

|

|

Lowry

724-C, 1999: Settling and erosion around the portal silo.

|

Even

as the underground beckoned me with its fantastic sights, I found it

hard to tear myself away from the silo doors, the unexplained shafts

leading into the darkness and lined with reflecting pools of water, and

the myriad other things I saw. Of course, when the site was opened

up and everyone was ready to go, all distractions on the surface were

forgotten.

|

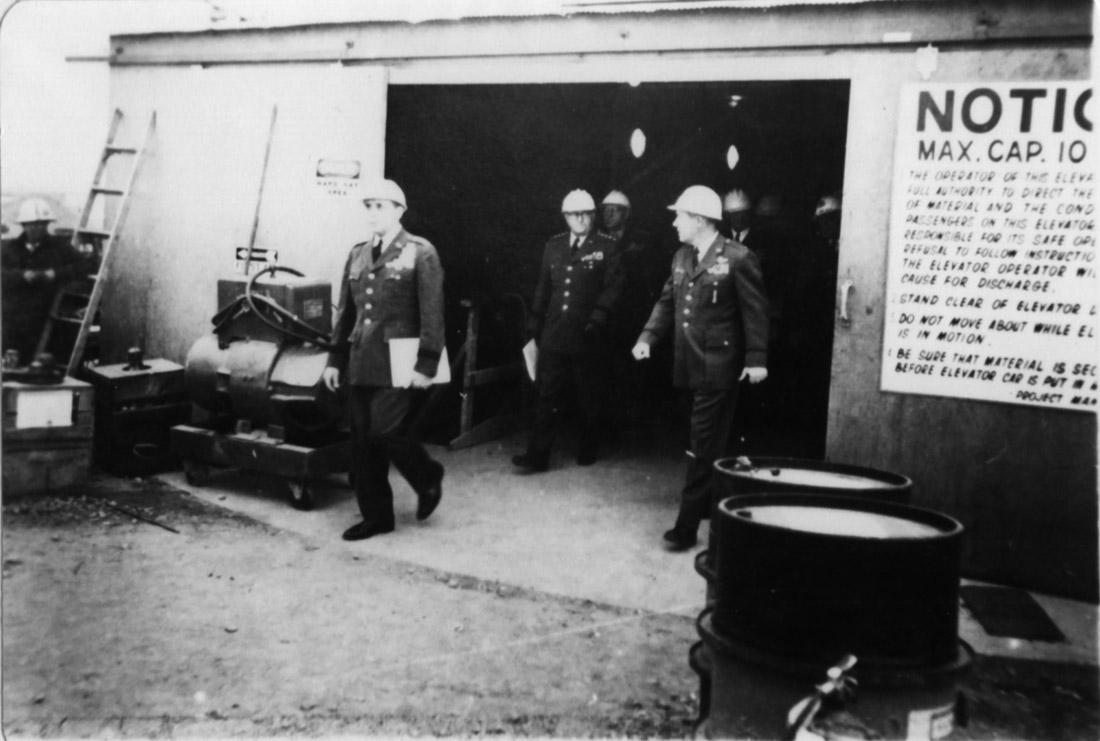

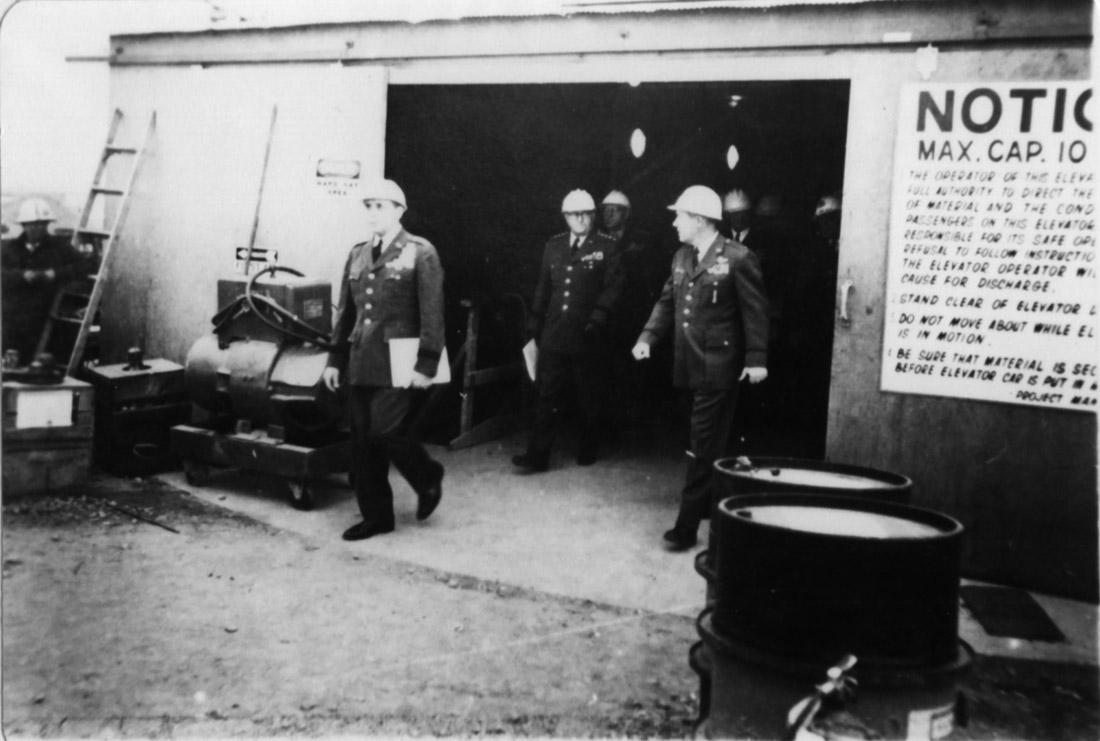

Lowry

724-A: Construction-era photo showing General Lymen Lemnitzer, Joint Chiefs

of Staff chairman (first on the left) and a contingent of high-ranking AF personnel exiting the entry portal.

(In spite of it's dual usage, "Entry/Exit Portal" was

undoubtedly discarded as too unwieldy a title.)

Behind

Gen. Lemnitzer in the glasses is Army Chief of Staff Gen. Decker and

Gen. White. Looking over toward Gen. Decker is Colonel Proctor who

is followed by Chief Naval Officer Admiral Arleigh Burk, making this

quite the group of heavy hitters in US military figures.

A temporary

surface building has been constructed over the portal silo during

construction. Looking more closely, two of the lights in the

elevator car can be seen through the doorway just above the officers'

heads near the top center of the photo.

When

I was at 724-C, I found the very same hand-painted sign as the one shown

at right in this photo lying in the grass near the antenna silos; faded,

peeling and riddled with bullet holes of course.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Mountain

Home, 1989: The entry portal silo doors standing open. You can see

here the sheer enormity of the doors' construction when viewed from the

side. Sections of the perimeter fencing appear to have been

scavenged for makeshift safety barriers for the open sides of the silo.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

My

very first look at a Titan 1 complex was quite different from what I

would see at 724-C . Years before I arrived at 724-C I was lucky

enough to get a look at 725-A, both inside and out. 725-A looked

quite different, and standing at the entry portal it looked positively

barren. Most of the landmarks of a Titan 1 site (unbeknownst

to me) seemed to be hidden, though at the time I would not have known

where to look for them.

|

Lowry

724-C, 1999: The instrument tube array, flush in the closed position.

|

|

A

closer view of the instrument tube array at 724-C: You can see some

power lines were routed into the facility by the contractors at the

site. After 724-C closed, a company occupied the site and

conducted testing both on the surface and in the underground

complex. At some point, they used the instrument tube to run

commercial power into the complex-- something which was not available

inside the site after salvage operations.

|

|

The

instrument array tubes fully deployed.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

724-B: Partially deployed instrument array tubes.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

724-B: It appears that the other two tubes are missing-- and that cart

is a long way from Safeway.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

The

Descent of Man

The

Impetus for heading underground-- beneath the Earth's surface-- was

obvious. As always, most developments in Man's history are driven

by war. With the advent of the Nuclear Age, it suddenly became

incredibly difficult and impractical to build a surface structure that

could survive an attack. When I say difficult

and impractical,

that really translates to expensive beyond measure.

Certainly solutions existed but they were stupendously costly and

required far more money and time

than anyone was comfortable with. To

alleviate this problem, the simple solution was to use the earth itself

to help shield men and their ability to conduct war from the dreaded new

menace from which there seemed-- duck

and cover notwithstanding-- no

defense. The solution was still stupendously expensive, but just

affordable enough to come to fruition.

And

so it was that bunkers and bomb shelters of old were found woefully

inadequate in terms of survivability once the genie was out of the

bottle and we were no longer the only kids on the block with the hottest

new toy. The game had changed, as it always does, and it seemed quite lucky that good old soil and stone was

fairly difficult to displace even with the most destructive weapons ever

devised; just put enough of them between you and your hardened facility

and your chances for survival and/or counter-attack greatly increased.

To

survive, you had to go deeper underground and use far more concrete and

steel-- even then a direct hit would cripple or kill just about

anything. Going underground was just part of the game. You

also had to play the numbers and spread yourself around hoping your

enemy would miss or not be able to target you in many different places

at once.

Thus

the underground missile complex was born, and early in the history of

missile defense, the Titan 1 would emerge in the furious tennis match

between nations as yield, accuracy, distance and clever methods such as

decoys, MIRVs and other innovations would trim the narrow margin for strategic

advantage again and again. This solution seemed quite adequate for

a time, or at least it was all that could be done on short notice.

In a few short years, projects of incredible scope and cost would

consume labor and raw materials, often outstripping supply in the race

to protect ourselves from

the weapon we had so hastily developed.

It

is this stage you are borne to immediately when you enter one of these

missile sites. Your imagination cannot help but conjure scenario

after scenario as you are literally engulfed-- submerged even-- in

history itself. It is impossible not to wonder about the people

who manned these weapons: what was it like to command such power,

and in contrast, to perform the mundane everyday tasks required of a

missile crew with their terrible responsibility?

What

was it like? How did it feel to be on a missile crew

and to tend to such forces, held deceptively in check? What could

it have been like to be on alert during the Cuban Missile Crisis when

the two most destructive arsenals on Earth could have been loosed upon

one another?

Only

the missile crews could ever know for sure.

To

everyone else, it seems impossible to understand; those days are gone,

the game has changed, but as you enter this concrete sarcophagus, you'll

get as close to knowing as you ever can.

Let's

go down deep into history and enter the lair of the Titans...

|

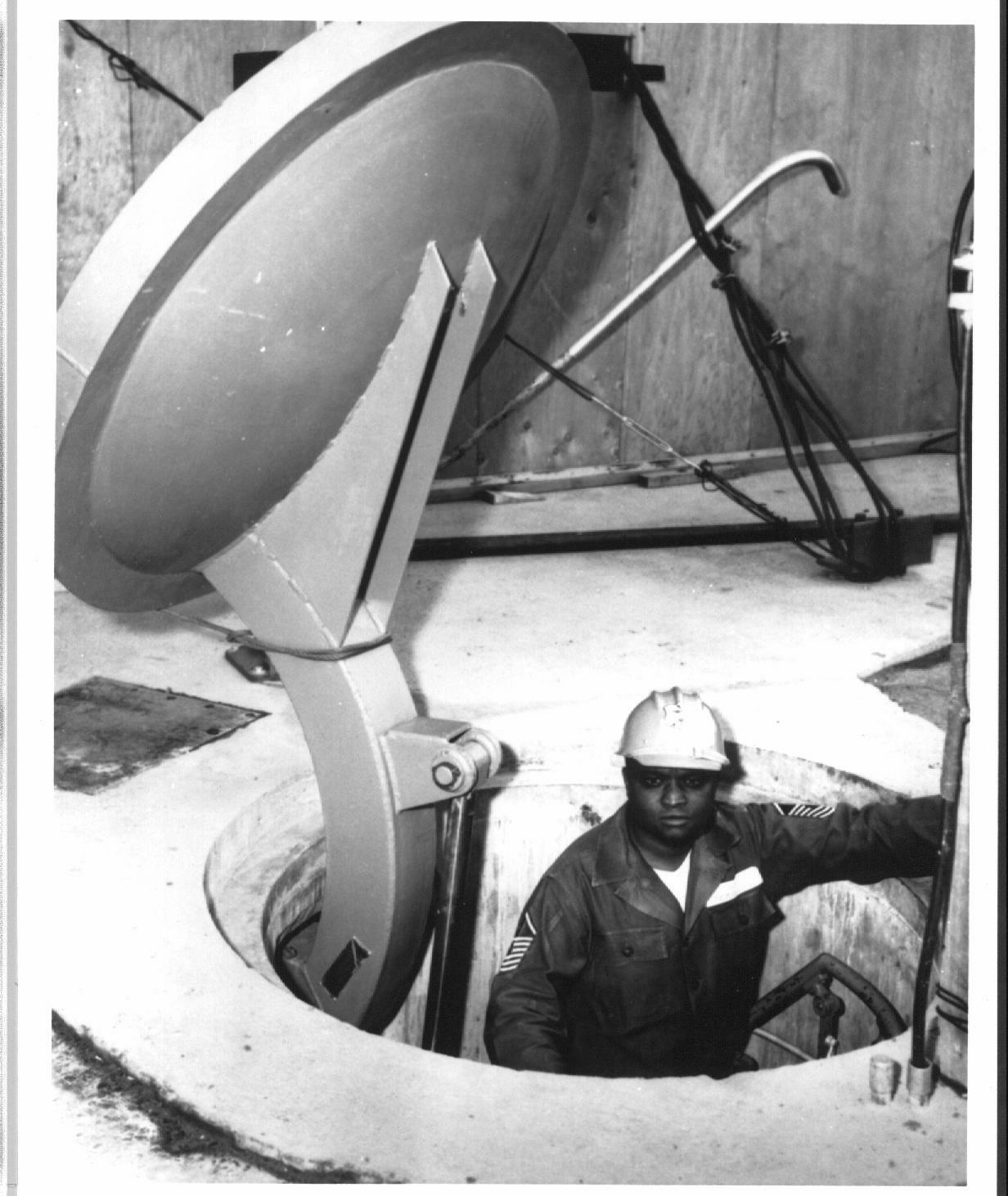

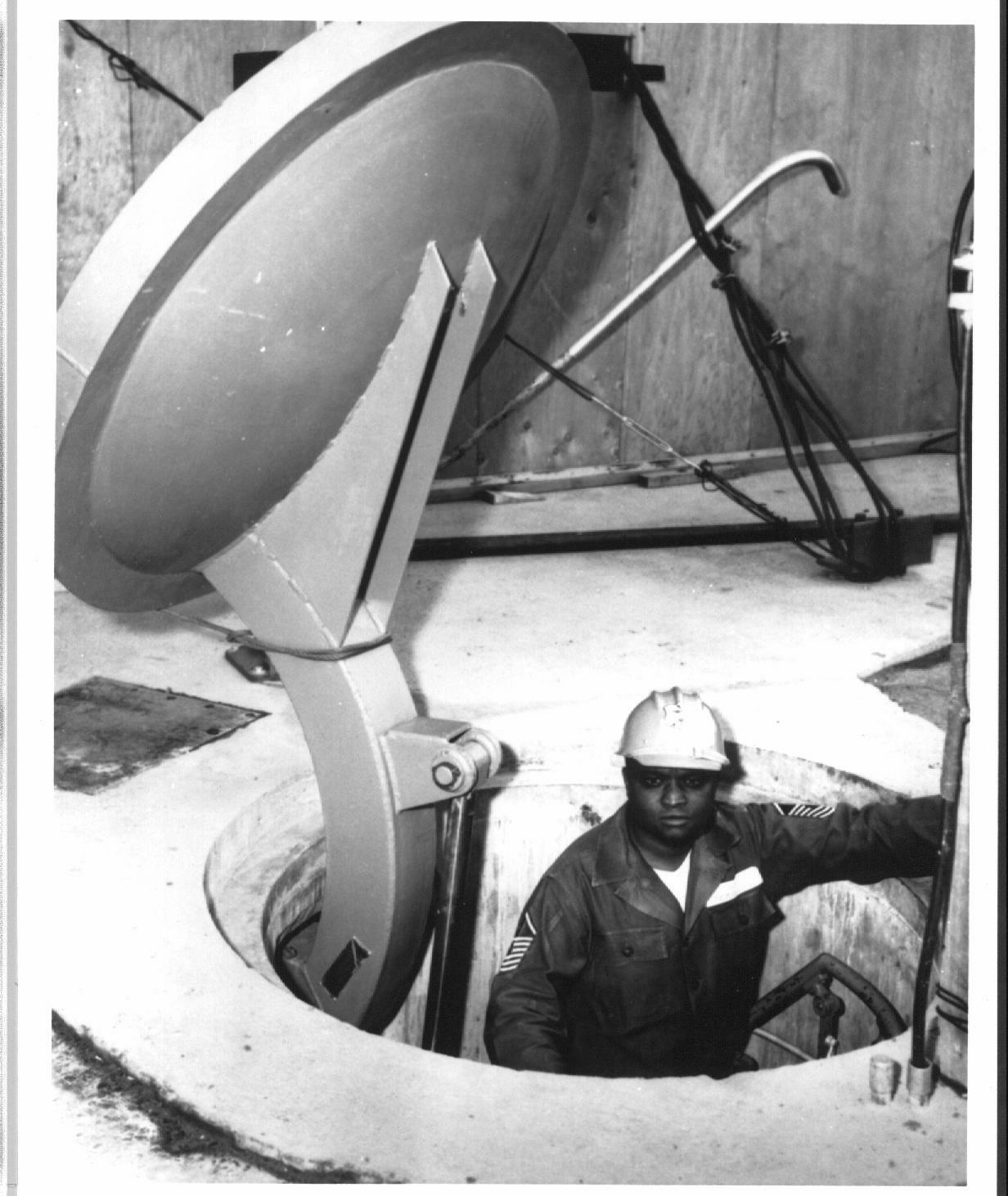

Construction

photo of the Titan I personnel entrance, circa 1960-61. Senior Master Sergeant

Abraham McMillan is shown here leaving the complex via the original

hatch. SMSgt. McMillan was a BMAT (Ballistic Missile Analyst

Technician) on launch crew R-01.

I quickly discovered that

the insignia the SMSgt. is wearing is now obsolete and it took me a

good hour to nail down what rank it represented. I went on to

state (quite incorrectly) that the insignia was changed in the 1960's--

a conclusion reached from sources on the internet. Live and learn

it turns out.

SMSgt.

McMillan's

insignia, a chevron with one stripe pointing up, and six pointing down, fell out of use somewhere in

1991 and was replaced with

the current design bearing two upward stripes and five downward

stripes. Details on how this change of insignia, which came about

through the creation of new "supergrade" ranks occurred was

graciously provided by Mike Jackson, SMSgt, USAF (Ret)

through his citation of the following linked document from the Air Force Enlisted Heritage Research Institute

by SMSgt. Michael L. Stewart, dated 22 July 1997. Read

it here.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

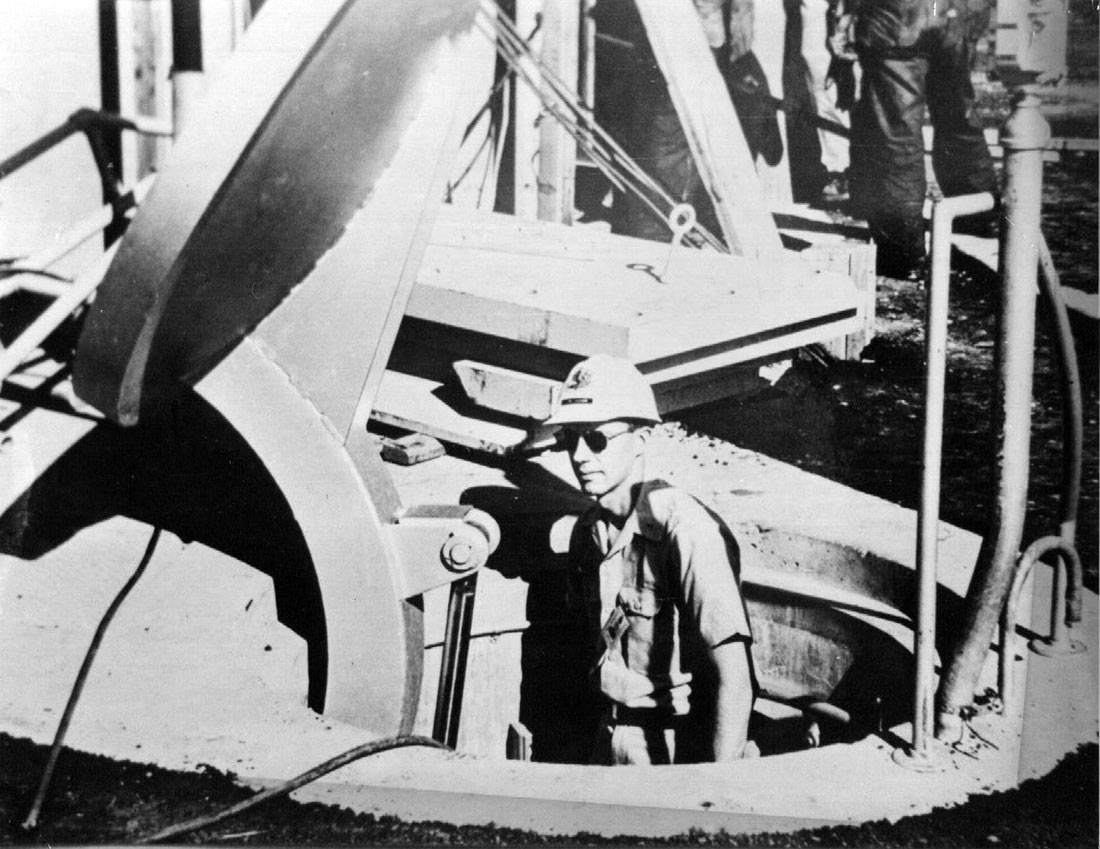

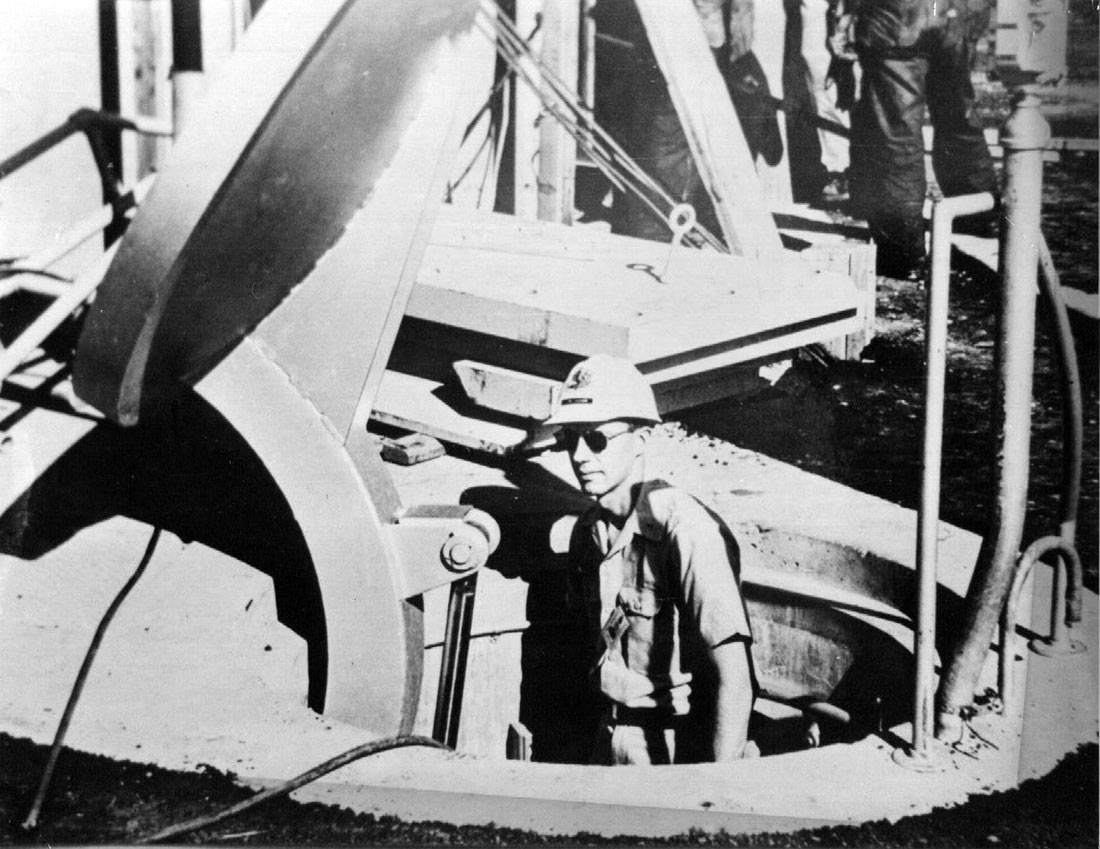

Unknown airman entering via the hatch and wearing completely different

khaki fatigues known as 1505's. Could be an officer-- after all, he's got those shades

on. Any info on the man in this photo would be greatly

appreciated. Contact

me.

There

is still some construction going on here as evidenced by the wires

running down the portal and lumber, etc. in the background.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

The

original hatch at Lowry 724-C, Winter 1999. In an attempt to stem

the flow of infiltrating water, the portal was covered in plastic, and

any crack, crevice or suspect cranny was filled with expanding foam

insulation. This proved futile of course as both plastic wrap, and

especially expanding foam, are very susceptible to the elements.

Wind and cold shredded the plastic and blew it away, and ultra-violet

light utterly disintegrated the foam in about a year's time. If

you look at the first image in this section you can just make out what

few tatters of plastic remain.

This

hatch has probably not been open since 1965 or earlier.

|

|

Lowry 725-A,

Winter 1986: Propped partially open, this site saw many, many

visitors over the decades after salvage. There is far more graffiti

inside it than perhaps all 5 of the other Lowry sites.

Photo

courtesy of Jim Despres

|

|

Lowry

725-A, 1986: For many many years, this entrance remained wide

open. There were a number of attempts to close up all entrances

into the site, the most recent being in 2005. The earlier efforts

were largely unsuccessful, but now this hatch is sealed and buried along

with the other routes into the complex.

Photo

courtesy of Jim Despres

|

|

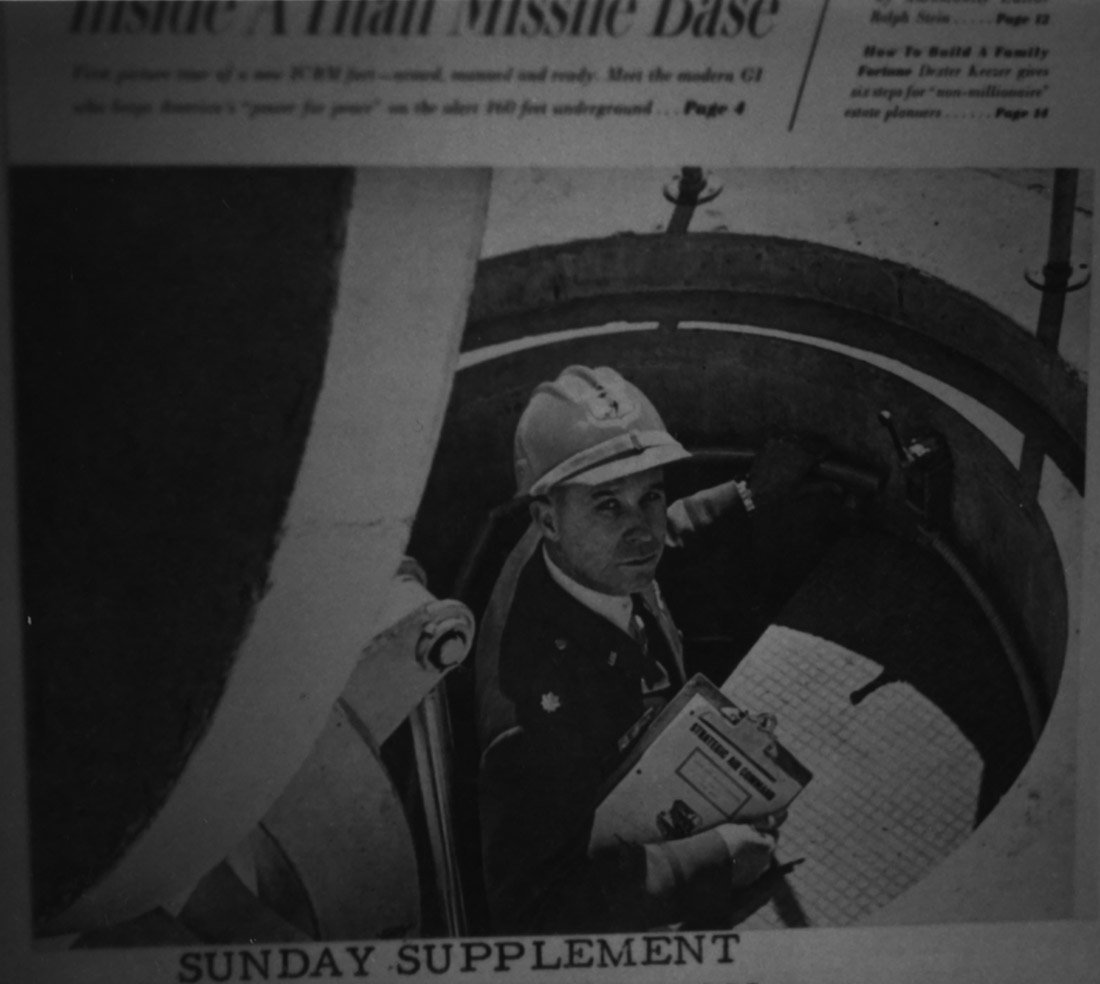

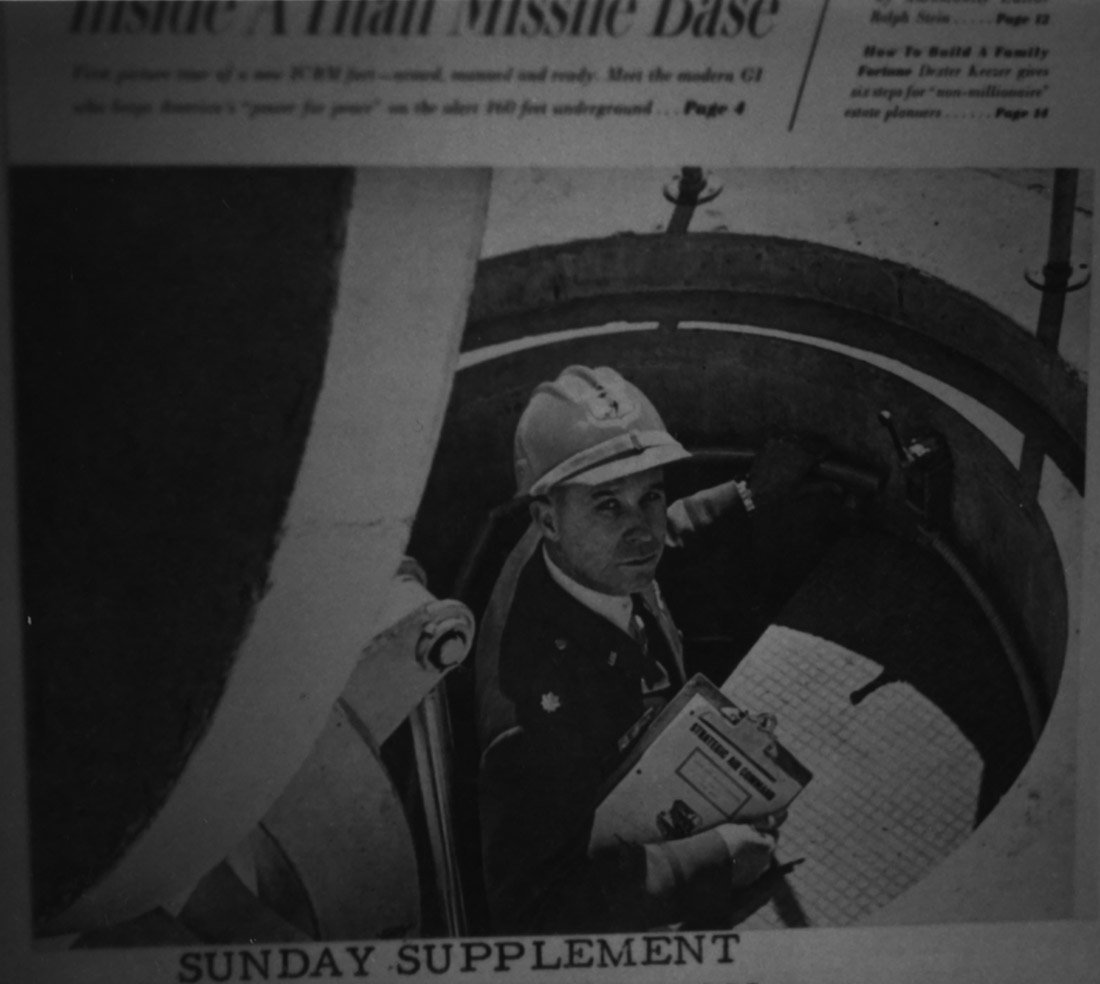

Lieutenant Colonel

Robert F. Simpson emerges from a Titan 1 complex on the cover

of This Week Magazine, a supplement of the New York Herald

Tribune featuring an exposť on the inner workings of

the missile system. Lt. Colonel Simpson was the first commander at

Lowry 724-B.

This photo is a nice view of the entry portal

showing the non-skid metal steps of the spiral stairs. Near Lt.Col.

Simpson's left hand is the limit switch that contacted with the closed

hatch to detect if it was open or closed.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Color

photo of the This Week Magazine cover. This article came out

shortly after the Lowry sites became operational. Click

here to read the full article.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

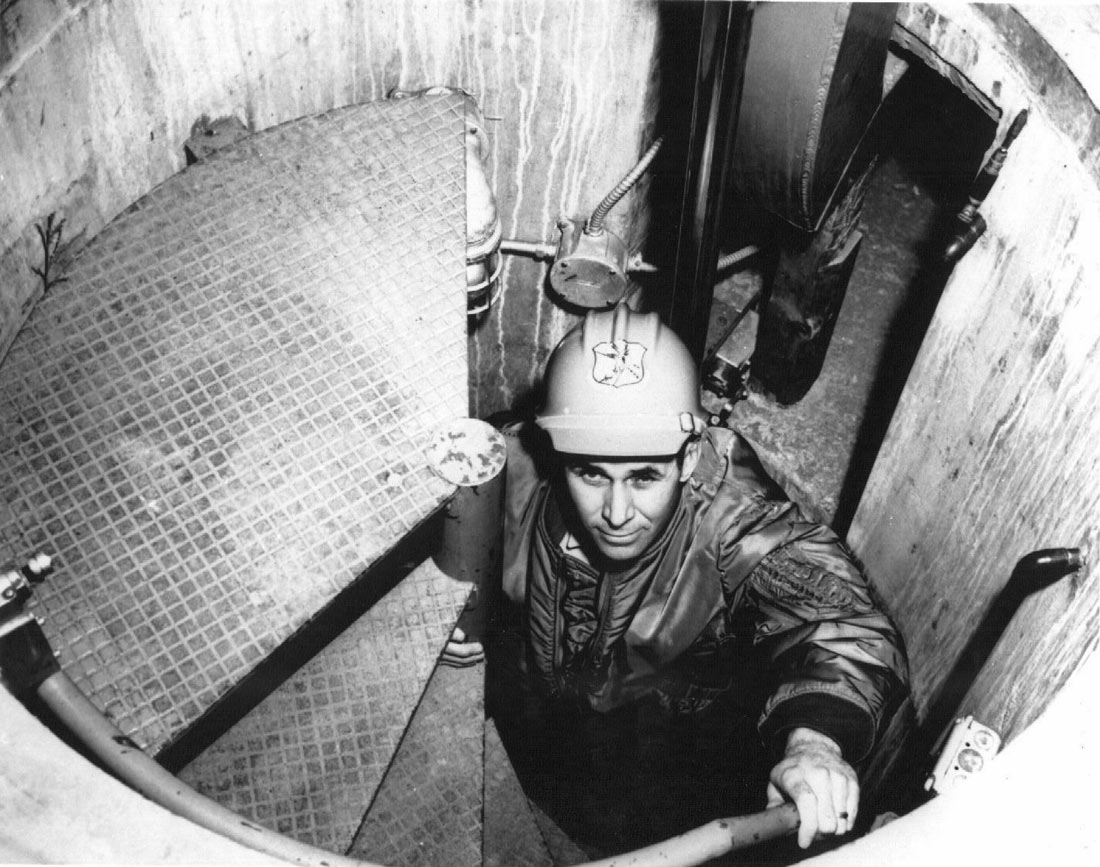

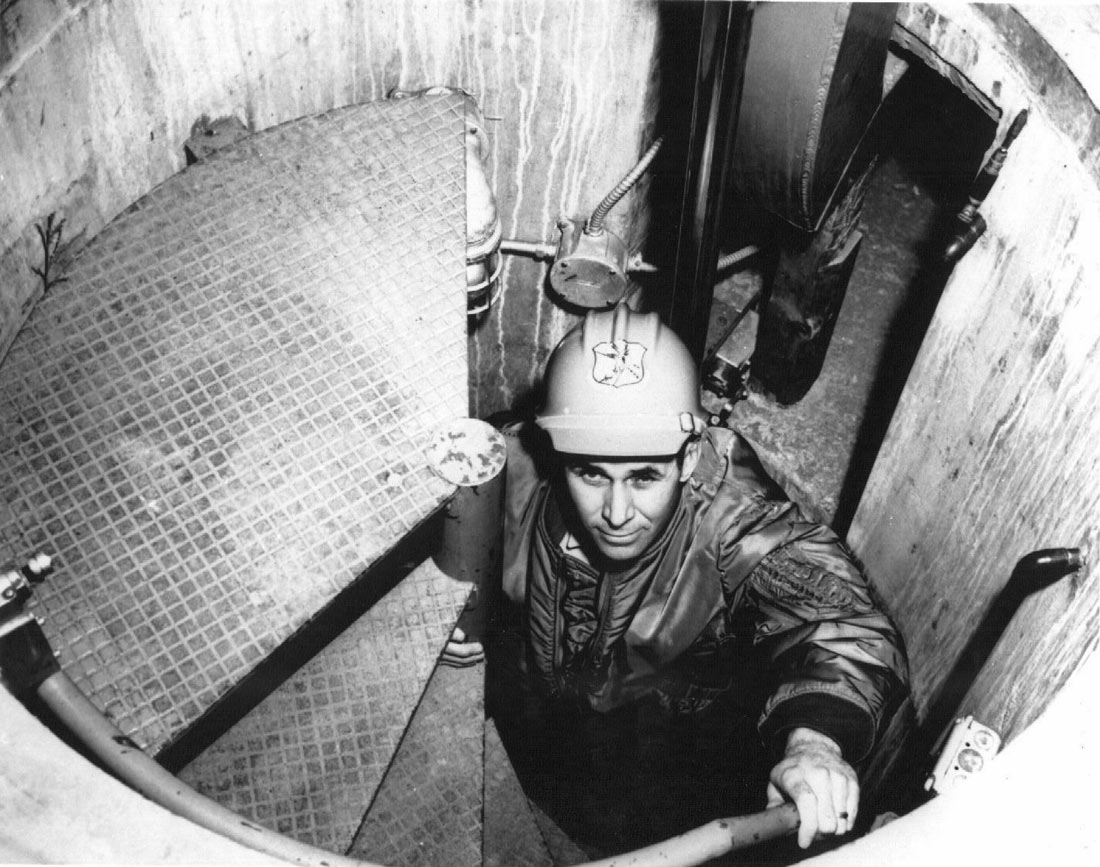

Captain

Don Smith makes his way up the steep and confined stairs of the

entry portal personnel entrance wearing his stylish flight jacket. The rather cramped and unsafe

nature of this entry would bring about its eventual abandonment early in

the sites' history. A larger entrance with a

set of regular steps and a new heavier cover would be hastily

retro-fitted to the sites, putting an end to the "gofer hole"

experience.

Captain

Smith was a GEO (Guidance Electronics Officer) with launch crew R-01.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

Originally,

entrance to the Titan 1 complex was through the round hatch shown in the

previous photos and down a set of

spiral stairs. This was later modified to the configuration shown

below for safety reasons. Apparently, the change came following a fatal accident

in 1961 at 724-C when a civilian worker slipped at the bottom of the

steps and was fatally injured by the revolving door.

Apparently

he was preceded by another worker that had just passed through the heavy

revolving door which was still moving when he fell into it. Certainly a

gruesome end, which would be more than enough justification for a

design change.

|

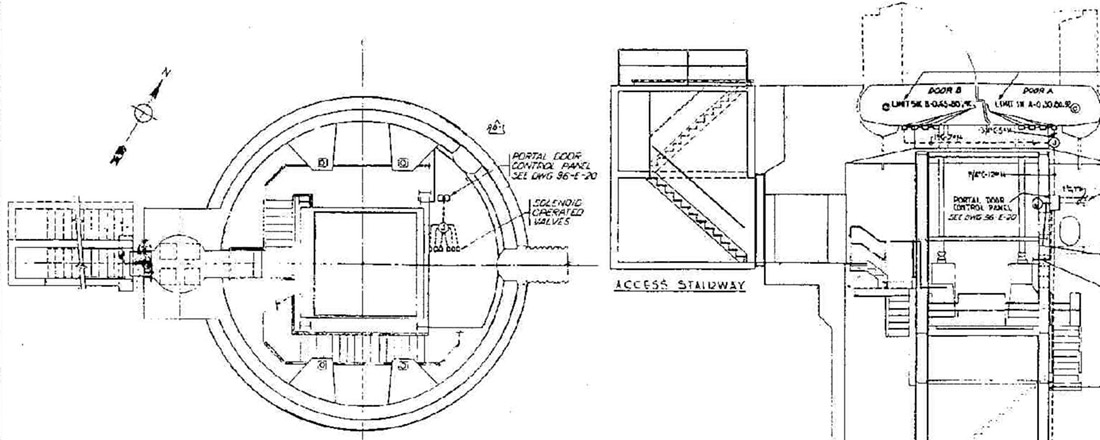

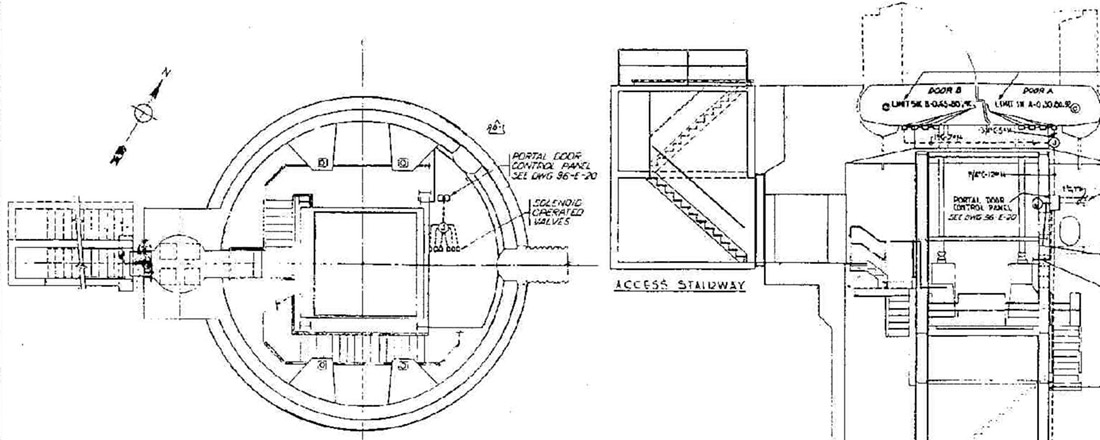

Blueprint

of the personnel entrance at one of the Mountain Home sites in Idaho

showing the re-worked, safer and much roomier design. This

replaced the decidedly more cramped and apparently dangerous design used

at the Lowry sites, which were the first to be constructed.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Looking

northwest: The newly-installed personnel entrance at one of the Lowry

sites. The new design used a concrete slab about a foot thick,

encased in heavy steel. The new stairs dispensed with the spiral

design and were much wider. The doors of launcher silo #1 are

visible in the background.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry:

Looking

southwest: Pristine asphalt and a clean new look about a very new Lowry

complex.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Looking

east: another look at the modified entrance and a glimpse of the freight

elevator peeking above the silo doors.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Looking

southeast: one last look at the personnel entrance and entry portal silo

doors.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

724-A: Old and new personnel entrances

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

As

these photos clearly show, at some sites, gaining entrance wasn't

exactly challenging. Attempts to secure the sites were made, but

often proved inadequate or underestimated the lengths to which the

curious will go.

Time

and time again, despite concerted efforts, teens, partiers, transients

and the aforementioned curious and missile-obsessed, thwarted just about

every obstacle placed before them and the Titan I complexes.

Around

1986, a kid broke his leg while exploring 725-A and finally,

crews were hired to try and batten down the many hatches of the Titans:

entrances were covered with concrete and steel; holes were filled in

with earth; steel was welded across openings; concrete blocks were

emplaced to hold hatches closed.

For

a while perhaps these things may have worked, but before long (and after

some careful thought perhaps) people came back and found new ways in or

worked on the new barriers with pry bars, sledge hammers and hack saws

until they failed.

|

Lowry

725-A, circa 1994: Site was opened up during an environmental

survey. You can see a large concrete block on the right that had

been down the hatch, and a concrete pad on the left that had been used

to cover the hatch opening. This very hatch was where my first

glimpse of a Titan 1 began.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

725-A, circa 1994: A closer look at the old personnel entrance.

The newer cellar stairs entrance is nearby, partially buried and covered

with the original steel and concrete lid.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

725-A, circa 1994: Replacing concrete blocks following an environmental

survey. When I arrived, the blocks were still in place but the

concrete pad had been moved. You can see the cellar stairs lid

partially visible on the lower left protruding from under the dirt.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

725-A, circa 1998: A bigger, tougher concrete pad blocks entry.

How long would this one last? You can see the edges are chipped

and broken, giving the appearance that determined forces have been hard

at work trying to dislodge this barrier. No matter, other ways

were found to gain entry, requiring further work to seal up the site in

2005.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

724-B: Steel and concrete hatch cover rests askew over the

entrance. That's a grain bin on the left-- this site has been used

for cattle grazing for many years. Part of the instrument array

can be seen next to the wooden shed in the background.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

724-B: This entrance has probably been more effectively closed since this

photo was taken. You can see that this dog could squeeze in

there, but a grown man of average size would probably find it very

difficult if not impossible to fit through there. However, a woman

of slight build from the Colorado Dept. of Health and Environment (CDPHE)

apparently could indeed fit through there. She encountered water

just a few feet down below.

Photo

courtesy of Fred Epler

|

|

Lowry

724-C, 1999: The heavy hatch cover lays some 50 feet away from the

entrance. A newer steel cover has been made to replace this much

heavier one.

|

I

never even saw the launcher silo doors during my visit to

725-A. I saw tall grass and weeds surrounding a rather

unremarkable hole in the ground. There was a cover for the hole

which was propped open with a wooden fence post. Looking down the

hole I could see dirt and large concrete blocks-- obviously placed there

for the express purpose of keeping curious folk like myself and my

companion from getting inside. These efforts were dreadfully

unsuccessful as the concrete blocks, which were too small to fill the

opening and left a gaping hole, did nothing to prevent our invasion, and

in fact, made descent much easier.

Handholds

and footholds galore were provided by the concrete blocks giving

precious purchase to aid in our exploration. We arrived at the bottom

without incident and confident of our ability to climb back out again

later.

We

stood on the vestibule of the great portal, our eyes adjusting, our ears

straining in the silence. A strange odor never before experienced

filled my nose; we were inside, but what was down there?. I had no idea what I was in for

and no clue how it would profoundly change my life.

We

turned on our flashlights and began to descend...

---------------------------

Next:

head into the underground complex and re-trace my steps as you

explore the dark depths of a nuclear missile's warren.

Click the link below or you can go to the Main

Map to explore elsewhere.

Entry

Portal section IV or Go

to Main Map

| Contact |

Site Map | Links

|

Hosted by

InfoBunker